Big lies, of course, reliably spring from money, power, and/or sex. The more outrageous they are, however, the more passionately we come to believe them. Count me among the befuddled. Why we believe these things, fall for the same scams over and over, and leave the liars and promoters free to scam again are among life’s great mysteries.

Take, for example, the grifter who, in the wake of the murder of Mormon founder Joseph Smith in the 1840s, took a lot of people for a ride. An atheist, James Strang decided he was Smith’s heir, complete with his own set of buried golden plates that only he could read. He regularly conversed with angels no one else saw or ever heard of. Like every charlatan, he asserted the times were even worse than people knew. Happily, he had the cure.

While the bulk of the flock chose to follow Brigham Young to Utah, Strang got enough people to believe him to earn a good living.

Swallowing the lie

Followers fell for Strang’s dog and pony shows even as he continued to bilk them, He took control of their wealth, set up a little kingdom of his own on Beaver Island in Lake Michigan, had himself anointed as king (king!), and, with each business failure, rumor of adultery and egregious lie, gained still more devotees. Soon he was better known for “consecrating” goods by stealing them.

Then he was elected to public office.

To me, not a little interested in history and politics, this sounded familiar.

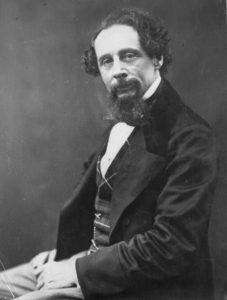

The marriage of grifting and shrewd business is hardly new in a society like ours’. The 19th century insight of Charles Dickens, as unearthed by Miles Harvey’s The King of Confidence, his book about Strang, seems as relevant an explanation of these mass snookerings as any.

Dickens (above), near the peak of his fame, was one of slew of European writers who came to see America in the 1840s. At the time, it was still a curiosity, with a reputation as a bold departure from the spangled monarchies, autocracies, and theocracies back home. Dickens arrived to collect material that ultimately would go into his American Notes and Pictures from Italy in 1846.

…And loving it

On the tour, he stumbled on to what appeared to be a strange American tendency to admire the thieves who snooker us. It happened on a visit to Cairo, Illinois. The locals called Cairo “care-o,” a linguistic quirk that might have indicated something was amiss.

At the state’s southern tip, Cairo promised a close look at America’s famous entrepreneurial gifts. It sat at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, an ideal spot for the very nexus of American commerce, loading and unloading the fruits of busy river traffic and surrounded by fertile farmland. It was bustling with opportunity.

What Dickens found, however, was “a dismal swamp, on which the half-built houses rot away… teeming with… rank and unwholesome vegetation.”

The author, like many of us who’ve followed, also wondered why the promoters who de-pantsed the public weren’t in jail.

In engineering the antebellum slum, the promoters of Cairo’s mythical prosperity had done very well. “I was given to understand that this was a very smart scheme by which a deal of money had been made,” Dickens wrote. It “lead to many people’s ruin.” Nevertheless, the takers weren’t crooked. They were clever. “Its smartest feature was that [victims] forgot these things in a very short time and [the liars] speculated again as freely as ever.”

He concluded it sprang from an inexplicable American “love of ‘smart’ dealing which gilds over many a swindle and gross breach of trust… and enables many a knave to hold his head up with the best.”

Hello, politics of 2021!

Meanwhile, back home…

Sadly, Cairo never did build back better. It’s still there in its seemingly blessed spot at the rivers’ confluence, but Atlas Obscura found it “mostly abandoned.” A mere 2,000 scattered residents remain, and nonetheless suffer a crime rate “much higher” than the average U.S. town. Cairo’s had a rugged racial history, too. Legends of America, a historical travel website, calls Cairo an example of “death by racism.”

The rank vegetation on its nearly deserted main street appears to have been uprooted, but business is slow. In early October, 2021, Zillow’s real estate listings for the town consisted of three houses for sale. One was a relatively new listing, on the market for 27 days. Another had been available for more than 100. The longest-tenured had already spent 385 days on the list.

Cairo exceptionalism, however, is as robust as ever. An arch over Commercial Avenue, its main street, triumphantly proclaims the bleak, nearly lifeless area “Historic Downtown Cairo.” Realtor.com touted another Cairo house for sale in an area known, without blushing, as “millionaires’ row.”

The Madmen May Change, But The Headlines Don't — Bill Sonn

[…] first place. Then, alas, these leaders proceed to go further around the bend Over and over again, we make the same mistake of accompanying […]